The peace of God, Christ is born!

If you are an Orthodox Serb living in the West, or if you have joined the Serbian Orthodox Church, you have probably noticed that the Christmas season brings many questions from friends and acquaintances.

The most common questions are almost always the same:

"Why do you celebrate Christmas on January 7th instead of December 25th?" If you invite your friends to experience the Christmas celebration for themselves, more questions arise:

Why do they light a large fire and why do they cut and burn an oak instead of decorating a fir tree?

Why is hay scattered on the church floor?

Why is bread baked with a coin inside?

Why does a male guest come to your home early in the morning and what exactly does he do?

And if your friend happens to be a Christian—especially a Protestant—you might hear a deeper question:

"What do all these traditions have to do with the birth of Jesus Christ? How is this even biblical?"

Spoiler: everything is so deeply rooted in the Bible that even your most devoted Protestant friend might be sincerely surprised.

In this text, we will try to answer all these questions, so that you can clearly explain to others the origin and meaning of Serbian Orthodox Christmas traditions, and perhaps learn something new yourself.

Why January 7th and not December 25th?

Let's start with the most frequently asked question.

Orthodox Christians indeed celebrate Christmas on December 25th, but according to the Julian calendar. In today's civil usage, December 25th on the Julian calendar corresponds to January 7th on the Gregorian calendar, which is officially used in most countries around the world.

So why not simply adjust our calendar to the Gregorian one and avoid confusion?

The full answer is complex, but a brief explanation goes like this: at the time of the birth of Jesus Christ, the Julian calendar was used. By continuing to use that calendar, the Church emphasizes continuity with the time of Christ and the apostolic era. It expresses the timeless character of the Church and its understanding that God's relationship with time is not the same as ours:

"For one day with the Lord is as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day" (2 Peter 3:8)

There is also a deeper spiritual awareness behind this choice: The Church does not seek to adapt to the world, but to Christ—even when it causes discomfort or misunderstanding:

"You are not of the world, but I chose you out of the world"

(John 15:19)

Traditions as the Language of the Gospel

To properly understand Serbian Orthodox Christmas traditions, we must first describe them in their original form, as they have been practiced for centuries in the regions where Serbs lived—primarily in villages—and then explain how they have adapted to modern urban life.

For most of history, Serbs lived close to nature. Hearths were central in every home, and access to forests was easy. Traditions developed naturally within that reality.

Tradition is not something separate from Scripture—it is The Word of God translated into a language that an ordinary person can understand. The Lord Jesus Christ taught in this way. When He spoke to shepherds and peasants, He explained the mysteries of the Kingdom of God using images that were familiar to them—sheep, lambs, fields, seeds, and shepherds:

"All these things Jesus spoke to the multitudes in parables… without a parable, He did not speak to them"

(Matthew 13:34)

Oak (Badnjak): The Renewed Tree of Life

Early in the morning on Badnje Veče, men from the house traditionally go into the woods to cut an oak (badnjak) and bring it home.

This tree symbolizes the Tree of Life, from which humanity was separated after the fall (Genesis 3:22–24). With the birth of Jesus Christ, the hope for eternal life is restored:

"I am the resurrection and the life"

(John 11:25)

At the place where the oak is cut, salt is left behind, as a symbol of the call for Christians to be "the salt of the earth" (Matthew 5:13). Wine is poured over the stump, representing the Blood of Christ, given for the life of the world (Matthew 26:28), and the wounds that heal us:

"By His wounds, we are healed"

(Isaiah 53:5)

When the men return home with the wood, women and children welcome them by throwing grain, fruit, and sweets - an expression of joy and blessings. This recalls the joy with which the shepherds and wise men welcomed Christ with gifts (Luke 2:15–20; Matthew 2:1–11) and His triumphal entry into Jerusalem (John 12:12–13).

Fire, Light, and the Cave in Bethlehem

In the evening hours of Badnji Dan, the oak is placed in the fire.

The light of the fire symbolizes the light that Christ brings into the world:

"I am the light of the world"

(John 8:12)

The fire also reminds of the warmth of the shepherd's fire near the cave in Bethlehem and foreshadows the sacrifice of Christ, who came into the world to give Himself for the eternal life of men (John 3:16).

Hay is scattered around the house, today in the church, creating the atmosphere of the cave in Bethlehem:

"She laid Him in a manger because there was no room for them in the inn" (Luke 2:7)

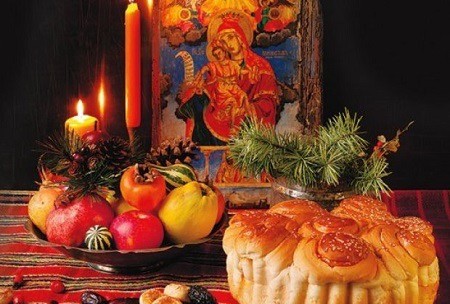

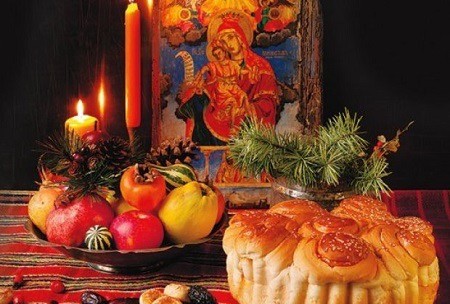

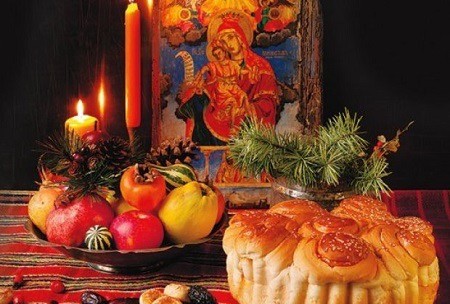

Česnica: The Bread of Life

On the fire, a special bread, called česnica, is baked, which is eaten on Christmas. The word comes from the Slavic čast, meaning honor, gift, feast, and blessing.

This bread clearly represents Christ, whose Body we receive and with whom we become one:

"Take, eat; this is My Body"

(Matthew 26:26)

Bethlehem literally means "House of Bread" (Beit Lehem in Hebrew), and it is right there that the true heavenly Bread was given to the world:

"I am the bread of life"

(John 6:35)

A coin is placed in the bread, and the one who finds it is considered blessed. The coin symbolizes the precious pearl of great value for which a man gives everything:

"The kingdom of heaven is like a merchant seeking beautiful pearls… who, when he had found one pearl of great price, went and sold all that he had and bought it"

(Matthew 13:45–46)

The Polaznik: The Apostle Who Brings Blessing

Early on Christmas morning, a male guest—traditionally a distant relative—comes home announcing:

"Christ is born!"

He approaches the fire, stirs it with a branch of oak, and blesses the home, saying that as many sparks fly out of the fire, so many blessings may fall upon the house.

This person, called položajnik or polaznik, represents the apostles, who went out into the world to preach Christ:

"As the Father has sent Me, I also send you"

(John 20:21)

The very term apostle means "sent one." With their arrival in the home, not just news enters but also blessings, and the light of Christ begins to shine:

"How beautiful are the feet of those who preach the gospel of peace"

(Romans 10:15)

A Living Tradition in the Modern World

Today, these traditions are practiced not only in villages but also in large cities, both in Serbia and in the diaspora.

Since most homes no longer have hearths, and scattering hay in apartments is impractical, the celebration increasingly takes place in churches. The Church becomes one big household, bringing families together.

Instead of cutting down their wood, people buy small branches of oak and burn them in front of the church. Some even burn one oak leaf on a plate in their apartment—just to experience at least a spark of the Christmas fire.

A Living and Universal Orthodox Witness

Serbian Orthodox Christmas traditions have not only survived centuries of history but have also adapted to modern life, continuing to convey a deep theological message: the mystery of Christ's birth, His sacrifice, Resurrection, and the apostolic mission of the Church.

For this reason, these traditions deserve not only to be preserved among the Serbian people but also to be shared as part of the universal heritage of Orthodox Christianity—a living testimony that the Word became Flesh and dwelt among us (John 1:14).

The most common questions are almost always the same:

"Why do you celebrate Christmas on January 7th instead of December 25th?" If you invite your friends to experience the Christmas celebration for themselves, more questions arise:

Why do they light a large fire and why do they cut and burn an oak instead of decorating a fir tree?

Why is hay scattered on the church floor?

Why is bread baked with a coin inside?

Why does a male guest come to your home early in the morning and what exactly does he do?

And if your friend happens to be a Christian—especially a Protestant—you might hear a deeper question:

"What do all these traditions have to do with the birth of Jesus Christ? How is this even biblical?"

Spoiler: everything is so deeply rooted in the Bible that even your most devoted Protestant friend might be sincerely surprised.

In this text, we will try to answer all these questions, so that you can clearly explain to others the origin and meaning of Serbian Orthodox Christmas traditions, and perhaps learn something new yourself.

Why January 7th and not December 25th?

Let's start with the most frequently asked question.

Orthodox Christians indeed celebrate Christmas on December 25th, but according to the Julian calendar. In today's civil usage, December 25th on the Julian calendar corresponds to January 7th on the Gregorian calendar, which is officially used in most countries around the world.

So why not simply adjust our calendar to the Gregorian one and avoid confusion?

The full answer is complex, but a brief explanation goes like this: at the time of the birth of Jesus Christ, the Julian calendar was used. By continuing to use that calendar, the Church emphasizes continuity with the time of Christ and the apostolic era. It expresses the timeless character of the Church and its understanding that God's relationship with time is not the same as ours:

"For one day with the Lord is as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day" (2 Peter 3:8)

There is also a deeper spiritual awareness behind this choice: The Church does not seek to adapt to the world, but to Christ—even when it causes discomfort or misunderstanding:

"You are not of the world, but I chose you out of the world"

(John 15:19)

Traditions as the Language of the Gospel

To properly understand Serbian Orthodox Christmas traditions, we must first describe them in their original form, as they have been practiced for centuries in the regions where Serbs lived—primarily in villages—and then explain how they have adapted to modern urban life.

For most of history, Serbs lived close to nature. Hearths were central in every home, and access to forests was easy. Traditions developed naturally within that reality.

Tradition is not something separate from Scripture—it is The Word of God translated into a language that an ordinary person can understand. The Lord Jesus Christ taught in this way. When He spoke to shepherds and peasants, He explained the mysteries of the Kingdom of God using images that were familiar to them—sheep, lambs, fields, seeds, and shepherds:

"All these things Jesus spoke to the multitudes in parables… without a parable, He did not speak to them"

(Matthew 13:34)

Oak (Badnjak): The Renewed Tree of Life

Early in the morning on Badnje Veče, men from the house traditionally go into the woods to cut an oak (badnjak) and bring it home.

This tree symbolizes the Tree of Life, from which humanity was separated after the fall (Genesis 3:22–24). With the birth of Jesus Christ, the hope for eternal life is restored:

"I am the resurrection and the life"

(John 11:25)

At the place where the oak is cut, salt is left behind, as a symbol of the call for Christians to be "the salt of the earth" (Matthew 5:13). Wine is poured over the stump, representing the Blood of Christ, given for the life of the world (Matthew 26:28), and the wounds that heal us:

"By His wounds, we are healed"

(Isaiah 53:5)

When the men return home with the wood, women and children welcome them by throwing grain, fruit, and sweets - an expression of joy and blessings. This recalls the joy with which the shepherds and wise men welcomed Christ with gifts (Luke 2:15–20; Matthew 2:1–11) and His triumphal entry into Jerusalem (John 12:12–13).

Fire, Light, and the Cave in Bethlehem

In the evening hours of Badnji Dan, the oak is placed in the fire.

The light of the fire symbolizes the light that Christ brings into the world:

"I am the light of the world"

(John 8:12)

The fire also reminds of the warmth of the shepherd's fire near the cave in Bethlehem and foreshadows the sacrifice of Christ, who came into the world to give Himself for the eternal life of men (John 3:16).

Hay is scattered around the house, today in the church, creating the atmosphere of the cave in Bethlehem:

"She laid Him in a manger because there was no room for them in the inn" (Luke 2:7)

Česnica: The Bread of Life

On the fire, a special bread, called česnica, is baked, which is eaten on Christmas. The word comes from the Slavic čast, meaning honor, gift, feast, and blessing.

This bread clearly represents Christ, whose Body we receive and with whom we become one:

"Take, eat; this is My Body"

(Matthew 26:26)

Bethlehem literally means "House of Bread" (Beit Lehem in Hebrew), and it is right there that the true heavenly Bread was given to the world:

"I am the bread of life"

(John 6:35)

A coin is placed in the bread, and the one who finds it is considered blessed. The coin symbolizes the precious pearl of great value for which a man gives everything:

"The kingdom of heaven is like a merchant seeking beautiful pearls… who, when he had found one pearl of great price, went and sold all that he had and bought it"

(Matthew 13:45–46)

The Polaznik: The Apostle Who Brings Blessing

Early on Christmas morning, a male guest—traditionally a distant relative—comes home announcing:

"Christ is born!"

He approaches the fire, stirs it with a branch of oak, and blesses the home, saying that as many sparks fly out of the fire, so many blessings may fall upon the house.

This person, called položajnik or polaznik, represents the apostles, who went out into the world to preach Christ:

"As the Father has sent Me, I also send you"

(John 20:21)

The very term apostle means "sent one." With their arrival in the home, not just news enters but also blessings, and the light of Christ begins to shine:

"How beautiful are the feet of those who preach the gospel of peace"

(Romans 10:15)

A Living Tradition in the Modern World

Today, these traditions are practiced not only in villages but also in large cities, both in Serbia and in the diaspora.

Since most homes no longer have hearths, and scattering hay in apartments is impractical, the celebration increasingly takes place in churches. The Church becomes one big household, bringing families together.

Instead of cutting down their wood, people buy small branches of oak and burn them in front of the church. Some even burn one oak leaf on a plate in their apartment—just to experience at least a spark of the Christmas fire.

A Living and Universal Orthodox Witness

Serbian Orthodox Christmas traditions have not only survived centuries of history but have also adapted to modern life, continuing to convey a deep theological message: the mystery of Christ's birth, His sacrifice, Resurrection, and the apostolic mission of the Church.

For this reason, these traditions deserve not only to be preserved among the Serbian people but also to be shared as part of the universal heritage of Orthodox Christianity—a living testimony that the Word became Flesh and dwelt among us (John 1:14).

The most common questions are almost always the same:

"Why do you celebrate Christmas on January 7th instead of December 25th?" If you invite your friends to experience the Christmas celebration for themselves, more questions arise:

Why do they light a large fire and why do they cut and burn an oak instead of decorating a fir tree?

Why is hay scattered on the church floor?

Why is bread baked with a coin inside?

Why does a male guest come to your home early in the morning and what exactly does he do?

And if your friend happens to be a Christian—especially a Protestant—you might hear a deeper question:

"What do all these traditions have to do with the birth of Jesus Christ? How is this even biblical?"

Spoiler: everything is so deeply rooted in the Bible that even your most devoted Protestant friend might be sincerely surprised.

In this text, we will try to answer all these questions, so that you can clearly explain to others the origin and meaning of Serbian Orthodox Christmas traditions, and perhaps learn something new yourself.

Why January 7th and not December 25th?

Let's start with the most frequently asked question.

Orthodox Christians indeed celebrate Christmas on December 25th, but according to the Julian calendar. In today's civil usage, December 25th on the Julian calendar corresponds to January 7th on the Gregorian calendar, which is officially used in most countries around the world.

So why not simply adjust our calendar to the Gregorian one and avoid confusion?

The full answer is complex, but a brief explanation goes like this: at the time of the birth of Jesus Christ, the Julian calendar was used. By continuing to use that calendar, the Church emphasizes continuity with the time of Christ and the apostolic era. It expresses the timeless character of the Church and its understanding that God's relationship with time is not the same as ours:

"For one day with the Lord is as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day" (2 Peter 3:8)

There is also a deeper spiritual awareness behind this choice: The Church does not seek to adapt to the world, but to Christ—even when it causes discomfort or misunderstanding:

"You are not of the world, but I chose you out of the world"

(John 15:19)

Traditions as the Language of the Gospel

To properly understand Serbian Orthodox Christmas traditions, we must first describe them in their original form, as they have been practiced for centuries in the regions where Serbs lived—primarily in villages—and then explain how they have adapted to modern urban life.

For most of history, Serbs lived close to nature. Hearths were central in every home, and access to forests was easy. Traditions developed naturally within that reality.

Tradition is not something separate from Scripture—it is The Word of God translated into a language that an ordinary person can understand. The Lord Jesus Christ taught in this way. When He spoke to shepherds and peasants, He explained the mysteries of the Kingdom of God using images that were familiar to them—sheep, lambs, fields, seeds, and shepherds:

"All these things Jesus spoke to the multitudes in parables… without a parable, He did not speak to them"

(Matthew 13:34)

Oak (Badnjak): The Renewed Tree of Life

Early in the morning on Badnje Veče, men from the house traditionally go into the woods to cut an oak (badnjak) and bring it home.

This tree symbolizes the Tree of Life, from which humanity was separated after the fall (Genesis 3:22–24). With the birth of Jesus Christ, the hope for eternal life is restored:

"I am the resurrection and the life"

(John 11:25)

At the place where the oak is cut, salt is left behind, as a symbol of the call for Christians to be "the salt of the earth" (Matthew 5:13). Wine is poured over the stump, representing the Blood of Christ, given for the life of the world (Matthew 26:28), and the wounds that heal us:

"By His wounds, we are healed"

(Isaiah 53:5)

When the men return home with the wood, women and children welcome them by throwing grain, fruit, and sweets - an expression of joy and blessings. This recalls the joy with which the shepherds and wise men welcomed Christ with gifts (Luke 2:15–20; Matthew 2:1–11) and His triumphal entry into Jerusalem (John 12:12–13).

Fire, Light, and the Cave in Bethlehem

In the evening hours of Badnji Dan, the oak is placed in the fire.

The light of the fire symbolizes the light that Christ brings into the world:

"I am the light of the world"

(John 8:12)

The fire also reminds of the warmth of the shepherd's fire near the cave in Bethlehem and foreshadows the sacrifice of Christ, who came into the world to give Himself for the eternal life of men (John 3:16).

Hay is scattered around the house, today in the church, creating the atmosphere of the cave in Bethlehem:

"She laid Him in a manger because there was no room for them in the inn" (Luke 2:7)

Česnica: The Bread of Life

On the fire, a special bread, called česnica, is baked, which is eaten on Christmas. The word comes from the Slavic čast, meaning honor, gift, feast, and blessing.

This bread clearly represents Christ, whose Body we receive and with whom we become one:

"Take, eat; this is My Body"

(Matthew 26:26)

Bethlehem literally means "House of Bread" (Beit Lehem in Hebrew), and it is right there that the true heavenly Bread was given to the world:

"I am the bread of life"

(John 6:35)

A coin is placed in the bread, and the one who finds it is considered blessed. The coin symbolizes the precious pearl of great value for which a man gives everything:

"The kingdom of heaven is like a merchant seeking beautiful pearls… who, when he had found one pearl of great price, went and sold all that he had and bought it"

(Matthew 13:45–46)

The Polaznik: The Apostle Who Brings Blessing

Early on Christmas morning, a male guest—traditionally a distant relative—comes home announcing:

"Christ is born!"

He approaches the fire, stirs it with a branch of oak, and blesses the home, saying that as many sparks fly out of the fire, so many blessings may fall upon the house.

This person, called položajnik or polaznik, represents the apostles, who went out into the world to preach Christ:

"As the Father has sent Me, I also send you"

(John 20:21)

The very term apostle means "sent one." With their arrival in the home, not just news enters but also blessings, and the light of Christ begins to shine:

"How beautiful are the feet of those who preach the gospel of peace"

(Romans 10:15)

A Living Tradition in the Modern World

Today, these traditions are practiced not only in villages but also in large cities, both in Serbia and in the diaspora.

Since most homes no longer have hearths, and scattering hay in apartments is impractical, the celebration increasingly takes place in churches. The Church becomes one big household, bringing families together.

Instead of cutting down their wood, people buy small branches of oak and burn them in front of the church. Some even burn one oak leaf on a plate in their apartment—just to experience at least a spark of the Christmas fire.

A Living and Universal Orthodox Witness

Serbian Orthodox Christmas traditions have not only survived centuries of history but have also adapted to modern life, continuing to convey a deep theological message: the mystery of Christ's birth, His sacrifice, Resurrection, and the apostolic mission of the Church.

For this reason, these traditions deserve not only to be preserved among the Serbian people but also to be shared as part of the universal heritage of Orthodox Christianity—a living testimony that the Word became Flesh and dwelt among us (John 1:14).